For most of my life, I measured growth by what could be seen—quantifiable achievements, public recognition, the relentless accrual of visible success. Growth, I believed, was a vertical pursuit—a climb toward the sun, higher and higher, as though life were a contest of altitude. I imagined myself as a young sapling, desperate to become a towering oak, convinced that every inch closer to the sky was a testament to my worth.

But experience has a way of unsettling such illusions. In time, I learned it is not the tallest tree that survives the storm, but the one with the deepest roots. And those roots do not thrive in the warmth of the sun. They grow in darkness, in the unseen chambers beneath the surface, pushing through resistant soil, twisting into spaces where no light reaches.

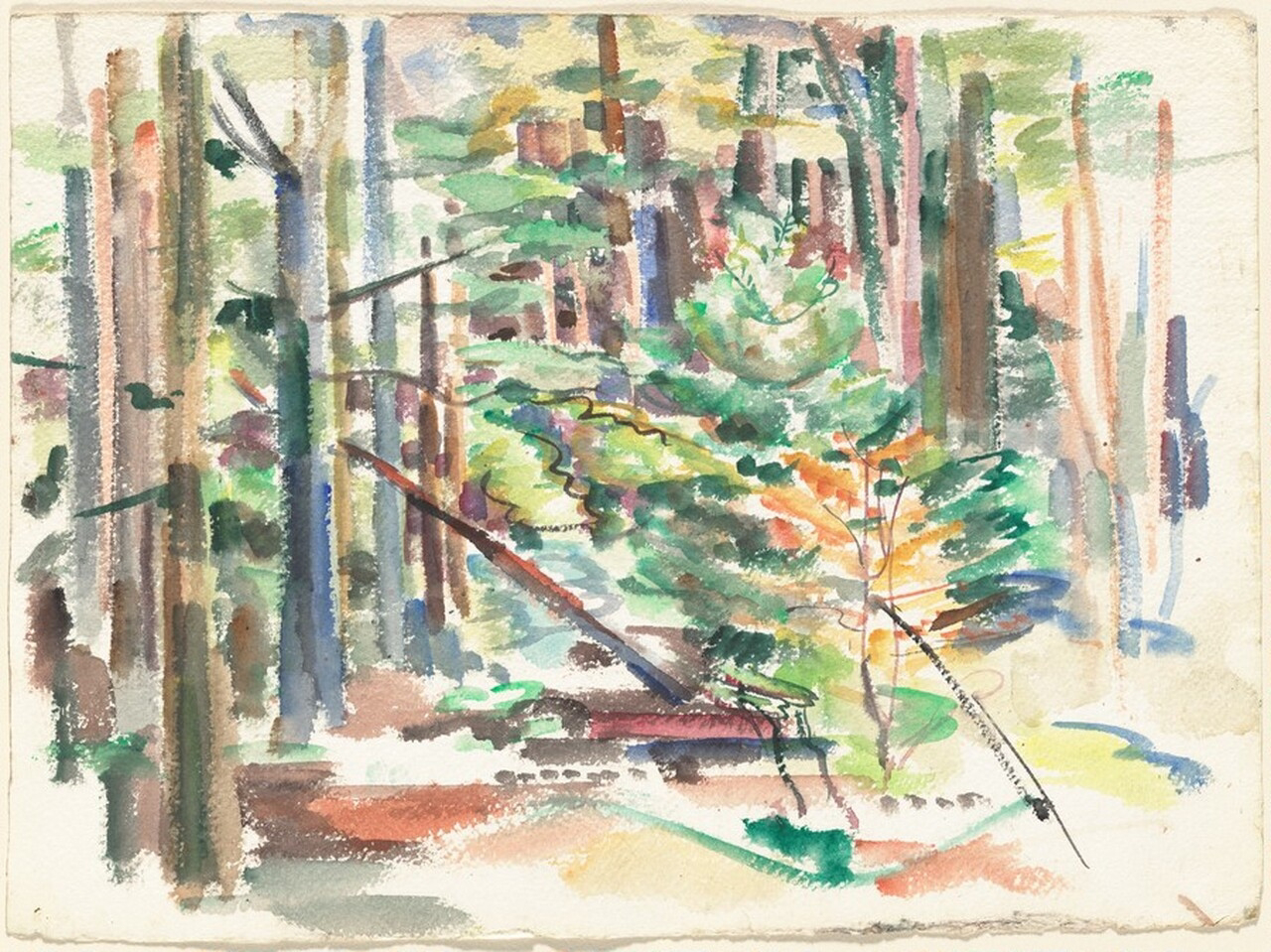

I return to this lesson each time I contemplate Mark Rothko’s Untitled (Forest Interior). Painted in 1933, before his mature abstract works, the painting presents a wild, unstructured vision of life—branches entangled, colors bleeding into one another, the landscape fractured and unresolved. Yet, what is most vital to the life of this forest—the roots—remains invisible. And perhaps that is Rothko’s most profound assertion: what matters most often escapes the eye.

We are conditioned to chase the visible canopy. Our culture valorizes the performance of success, the curated image, the polished outcome. But as Nelson Henderson observed, “The true meaning of life is to plant trees under whose shade you do not expect to sit.” This is the ethic of unseen labor—of investing in the slow, hidden work that will bear fruit long after we are gone, and perhaps in ways we will never witness.

Nature makes no such mistake in its accounting of strength. Consider the redwood forests of California. Their grandeur is not merely a spectacle of vertical ambition but a marvel of interconnected humility. Beneath the soil, their roots spread wide and entangle with others, forming vast networks of mutual support. Botanists call this the mycorrhizal network—a complex system through which trees share nutrients and warnings, sustaining each other against drought and disease.

This is not the solitary heroism we are taught to idolize. It is the quiet, collective resilience forged through unseen bonds. A life of true depth is not built upon public triumphs but through small acts of generosity, the private cultivation of patience, the forgiveness offered without recognition.

Even adversity, often regarded as a hindrance to growth, becomes in this paradigm a necessary force. Seneca wrote, “No tree becomes rooted and sturdy unless many a wind assails it.” The storm is not the end of growth but its proving ground. Without hardship, roots remain shallow; without resistance, there is nothing to press against, nothing to strengthen the unseen self.

Yet we so often flee from the very darkness that would make us strong. Psychologist Carl Jung understood this avoidance of inner struggle as the rejection of the Shadow—the hidden parts of ourselves we refuse to acknowledge. We favor the curated self, the self fit for public consumption, while neglecting the deeper, often painful labor of self-examination. But as Jung warned, “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.” It is precisely in these shadowed regions that our roots take hold.

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke articulated this inner calling when he wrote, “The work of the eyes is done. Go now and do the heart-work on the images imprisoned within you.” The heart-work—like the slow, patient labor of roots—does not adorn our lives with immediate beauty. But it anchors us when all else fails, when the bright canopy of our carefully managed successes has been stripped away.

I think now of the years I once dismissed as stagnant. Periods without advancement, without public recognition. I called them wasted time. But in truth, those were the years I learned how to be still with my failures, how to forgive when reconciliation was impossible, how to cultivate virtue without the promise of reward. Those were not lost years. They were years of root work. And they saved me.

In the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, there is an acceptance of imperfection, a reverence for the incomplete and the transient. A cracked teacup mended with veins of gold becomes more valuable for its scars. So too, a life that has weathered hardship and emerged resilient possesses a beauty far richer than a life untouched by suffering.

Looking once more at Rothko’s chaotic forest interior, I see not confusion but the truth of how life unfolds—messy, uncertain, tangled with moments of loss and redemption. The roots are not drawn, but they are implied everywhere, silently holding the scene together.

We have been taught to admire what reaches highest. But perhaps it is time we learn to ask different questions: How deep have I grown? What unseen virtues have I cultivated? What storms am I prepared to endure because of the quiet labor I have done in the dark?

Let us grow deep before we grow tall. And when we do rise, let it be not for applause, but because we are rooted deeply enough to stand.

For what good is it to touch the sun if a single strong wind can bring us to the ground?