This week, two different groups came to my door. The first were two young women from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The second, two men from a Southern Baptist church. They arrived without warning but not without purpose. Both came bearing pamphlets, smiles, and certainty. I met them with politeness—but also with the weight of my own story. It is hard to say "no" when your life has been shaped by so many years of saying "yes" out of fear, guilt, or obligation. It is hard to close the door without also feeling the echo of a slammed sanctuary.

The young women were gentle, practiced. They had known rejection. They were, in many ways, still girls. Their presence reminded me not of conquest but of training, of ritual, of obedience. They did not press. They asked if I would pray with them. I declined. They left with a smile that felt real, even if rehearsed.

But the older man from the Baptist church came like a general. He was not there to visit. He was there to win. His posture was firm, his voice unwavering. He did not come to love, but to argue. I did not feel compassion. I felt intrusion. When I said I wasn't interested, he pressed. When I tried to deflect, he sharpened. He did not seem to care who I was, only that I was not yet who he thought I should be. I saw not a shepherd, but a sword.

When I was 17, I went on a World Changers trip to Birmingham. We built homes, we painted tin roofs, we handed out water and food. And we witnessed. Before leaving, we were taught the Shoot the Bull method—a way to build trust and rapport before walking strangers down the Roman Road and leading them in the Sinner's Prayer. At the time, I believed we were doing good. I believed we were saving lives. But now, years later, I see it differently. I remember the pressure to convert, the subtle way love was measured by results. I see now that we were not taught to listen. We were taught to persuade.

As I’ve grown older, I’ve come to value listening far more than speaking. I no longer see relationships as a means to an end—not as potential conversion points or moral victories, but as sacred encounters, worthy in themselves. There was so much hustle in the way I was taught religion. So much urgency. The need to save, to change, to win. Evangelicalism taught me to move fast, speak first, and plant flags. But now, as a more mature man, I have rejected that part of my upbringing. The noise has quieted.

The pitfalls of evangelism, as I now see them, lie not only in their methods but in their assumptions. Evangelism begins with a conclusion: that I have something you lack, that my truth must become your truth, that salvation is a transaction I can broker. It demands urgency, certainty, and control. But what it often neglects is relationship—authentic, reciprocal relationship. It assumes that love means changing someone, rather than understanding them.

My rejection of that version of religion—one rooted in urgency and conquest—has shaped who I am today. I no longer feel the pressure to be right. I no longer view people as spiritual projects. Instead, I strive to be present, to be curious, to be compassionate.

Psychologically, active listening is a profound shift in orientation. It requires the suspension of judgment and the silencing of our own internal dialogue. Carl Rogers, the father of humanistic psychology, believed that "when someone really hears you without passing judgment on you, without trying to take responsibility for you, without trying to mold you, it feels damn good." And it does. Listening validates. It dignifies. It makes room for others to exist as they are, not as we wish them to be.

Active listening engages multiple layers of the brain—from the limbic system, where emotion resides, to the prefrontal cortex, where empathy and ethical reasoning are processed. It slows us down. It builds trust. It makes possible the kind of vulnerability that evangelism often short-circuits.

And in that shift—from speaking to listening, from convincing to connecting—I have found peace.

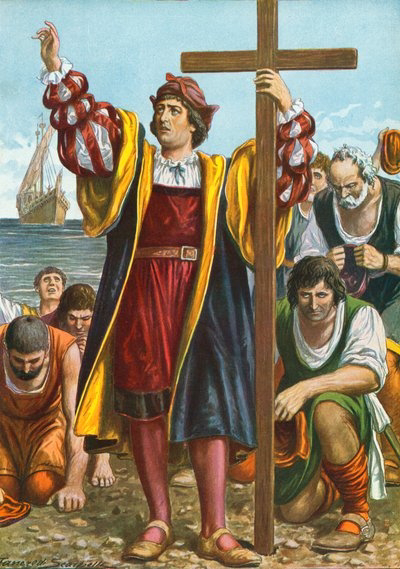

It is in this context that I looked again at Tancredi Scarpelli's painting, Christopher Columbus Arriving in the New World. There is no ambiguity in the scene. Columbus stands with a cross in hand, flanked by men who bow, kneel, or gaze reverently. Behind them, the ship still floats, its sails furled like banners of arrival. This is not exploration; it is declaration. The land is not discovered; it is claimed.

That cross he plants could just as easily be the one held by the man at my door.

The painting is bold in its color and composition—vivid reds, radiant yellows, the gleam of conquest. It is not a peaceful moment. It is performative. Columbus does not merely step onto the shore; he orchestrates a scene. It is a theater of dominion. And in it, I saw my week reflected.

Missionaries, like conquerors, come bearing certainty. And certainty is a dangerous thing when it cannot hear, cannot bend. I do not fault the desire to share joy, or peace, or hope. But I know the cost when that desire becomes imperial. When belief becomes entitlement. When the home becomes a battleground.

Thomas Merton once wrote, "The beginning of love is the will to let those we love be perfectly themselves." But what I encountered this week was not that. It was not love. It was ideology with teeth.

There is a difference between witness and conquest. Between invitation and invasion. I wish more knew the difference.

And I, for my part, am learning to defend my shoreline. To be kind without surrender. To recognize the colonizer's cross when it appears, even if it comes with a smile. Maybe my soul is not a mission field. Maybe it is already inhabited, already sacred. Not in need of conquest, but of peace.