The first day off after a long school year is unlike any other. It carries a silence that feels earned, as if the world finally agrees to let you exhale. This morning, I did not wake to an alarm or a lesson plan. No bells rang. No emails blinked. I woke to stillness and the soft shift of fur against my ankles—my cats, already masters of rest, reminding me how to begin.

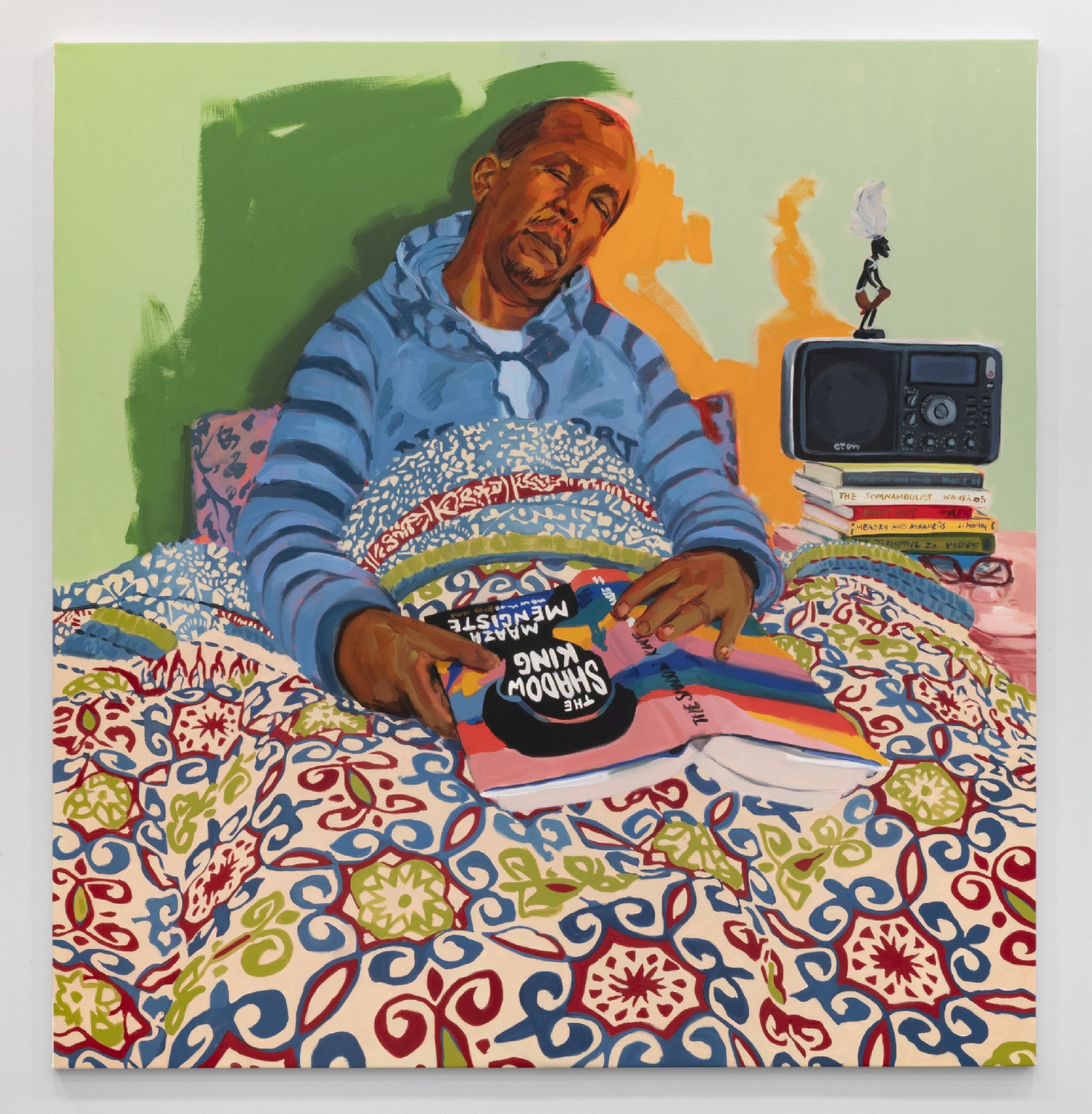

Rest, I’ve learned, is not a reward. It’s a necessity. A reclamation. In a culture that glorifies productivity, pausing feels transgressive. But today, I am leaning into the pause with intention. I’m reminded of Wangari Mathenge’s painting Regarding Reverence, Resistance and Respite, in which a man rests fully clothed in bed, still holding a book, surrounded by color, memory, and warmth.

It’s a quiet scene, but it hums with life.

The patterns of the quilt are bold and busy—florals, curls, and mandalas of color—and they almost seem to pulse, as if they’re the true subject of the painting, a visual reminder that home is layered. That peace is complex. That even when the body stops, the mind continues to dream. His hand rests on a copy of The Shadow King, the pages slightly open, as though he meant to keep reading but trusted the moment to carry him into sleep.

That’s what today feels like for me: a surrender not to exhaustion, but to the fullness of home.

The school year asks so much of us. We pour ourselves out daily—in discipline, in care, in planning, in patience. Summer school asks again. And then, one day, it ends. And on that first free day, when the rhythm of bells no longer governs our time, the question arises: what now?

For me, the answer is this: I travel. I visit the places I love. I seek out sun and sky and the particular stillness of long roads stretching west. But I also return home, again and again. I sit with my family over drawn-out meals, without the clock tugging at us. I find joy in watching my cats stretch into their windowsill spots, content and unrushed. I spend entire afternoons doing nothing of measurable value and find in them something immeasurable.

Mathenge’s painting understands this balance. It speaks to the sacredness of the everyday, the power of comfort not as retreat, but as resistance. Rest here is not idle—it is active, chosen, protective. And it raises a subtle but important question: who gets to rest? Who gets to feel at home? Who gets to be still without guilt?

In this moment, I do. And I do not take that lightly.

I think of the words of Tricia Hersey, founder of The Nap Ministry:

“We will rest. We will resist. We will imagine. We will be.”

So today, I let myself be. The school year is over. The papers are graded. The classrooms are dark. And I am home—with my cats, my books, my time, and the sweet, slow knowledge that this rest is not a pause between chapters. It is the chapter.